Oviposition Behavior of Yellow Stem Borer (Scirpophaga incertulas) and Rice Bug (Leptocorisa oratorius)

| Authors | Kimber Jann G. Adraneda, Atiyyah G. Herrera, Jenny Faith J. Sanchez, Aluel Paolo H. Gonzaga, Julliene M. Magsico, Phillip Raymund R. De Oca, Gerald E. Bello & Leonardo Marquez |

|---|---|

| Volume | 2 |

| Date Published | May 16, 2024 |

| Date Updated | May 16, 2024 |

Abstract

The oviposition behavior of Yellow Stem Borer (YSB) and Rice Bug (RB) on various rice varieties were assessed in this study to mitigate negative factors affecting the yield of crops. The conduct of the research experiment was divided into various phases: pre-experimental preparation, on field procedure, and data analysis. Thirteen rice cultivars (NSIC Rc 216, NSIC Rc 480, NSIC Rc 442, NSIC Rc 222, NSIC Rc 160, NSIC Rc 534, NSIC Rc 506, NSIC Rc 27, PSB Rc 18, PSB Rc 82, Arabon, Calatrava, Cuevas) with varying levels of resistance and susceptibility to YSB and RB were used in the study. The insects were provided with a choice of rice varieties, and their egg-laying preferences were carefully monitored and recorded. Significant variations in the quantity and measurements of oviposited eggs between the subject species in different susceptible rice varieties were observed. Rice varieties with good eating quality (NSIC Rc 27, Arabon, NSIC Rc 216, PSB Rc 18, Calatrava, and NSIC Rc 480) exhibited higher susceptibility to egg-laying, while lower preference were displayed in (NSIC Rc 442, NSIC Rc 222, NSIC Rc 160, PSB Rc 82, NSIC Rc 534, NSIC Rc 506 and Cuevas). The plant morphology of the rice varieties appeared to significantly influence the pests' preferences and vulnerabilities.

Introduction

Yellow Stem Borer (YSB), a monophagous nuisance of paddy is regarded as a maximum vital pest of flood-susceptible and rain-fed lowland rice eco-structures, consisting primarily of insects in the family Pyralidae [1]. They have a small yellow-brown body with a wingspan ranging from 16-25 mm and display two to three dark spots on their white-yellow forewings [2]. YSB is widely distributed in the tropics but also found in temperate regions if the annual rainfall exceeds 1000 mm and the temperature is consistently above 10°C, causing continuous infestation in dry and wet seasons [3]. Throughout the province of Negros Occidental, during outbreaks, yield losses caused by YSB may range from 25% to 50%. According to reports, they consistently cause 5–10% of the annual damage to the rice crop, with catastrophic recrudescence accounting for up to 60% of the losses locally [4][5]. Deadheart and Whiteheads are the two prominent indications of yellow stem borer infestation in rice crops during the vegetative and reproductive stages. Whiteheads exhibit panicle discoloration and hollow or partly filled grains, while deadhearts causes the withering of the central whorl [6]. Rice Bug (RB), a sap-sucking pest of paddy is considered a major threat in all rice ecosystems, consisting primarily of insects in the family Alydidae [7]. They are shield-shaped, light yellow-green to yellow-brown in color, having a single sharp spine in each shoulder ranging 14-17 mm long and 3-4 mm wide [8]. RB thrives more quickly under warm climatic conditions, with the minimum development threshold temperatures at 12°C and 14°C [9]. Throughout the province of Negros Occidental, rice bug is a widely distributed occurring pest in certain municipalities causing approximately 20% damage to the local rice field [10][11]. Rice Sheath Rot is one of the indications of infestation by allowing fungi to enter the stem and corrupt the endosperm of the grain throughout the feeding process [12], causing the plant’s sheath to rot which results in unfilled, shriveled or partially filled grain [13]. Another indicator is the offensive odor that the rice bug emits from the scent glands on its abdomen in infected rice crops [14]. Modern agriculture is primarily dependent upon the substantial utilization of synthetic pesticides [15]. The sustainability of crop production has been significantly enhanced over the past century by employing this strategy against insect pests. Nevertheless, this approach is solely intended to maximize grain yield, disregarding long-term effects including the deterioration of soil, increasing emissions of greenhouse gasses, and a decline in water quality and supply [16]. The search for innovative pest control methods to limit the use of synthetic pesticides and establish better ecologically friendly production systems has drawn attention worldwide. One alternative method tackled in previous literature [17] is to explore further the oviposition behavior of insect pests prevalent on cultivars. Despite its importance, there is a significant gap in the attainment of information regarding the holistic aspect of egg-laying behavior and how it contributes to the species' survival and spread. Oviposition behavior is the process of the ovipositor choosing where to deposit their eggs in their preferred host plants, leading to egg hatching [18]. The growth of destructive insects that bore into the rice stem, leads to growth retardation, poor grain quality, or worse, complete crop failure [19]. Thus, controlling the spread of Yellow Stem Borers and Rice Bugs on rice crops is crucial to protect the livelihoods of farmers who rely on rice production for their income, as well as to ensure food security for populations that depend on rice as a sustainable food crop [20]. The main objective of this study is to investigate the oviposition behavior of Yellow Stem Borer and Rice Bug in rice cultivars as a logical approach to mitigate negative factors affecting the yield of crops. Specifically, it aims to observe the number of egg masses and eggs per egg mass, length and width of egg masses, varying length and width of the leaf, preferential side of egg masses in the parameters upper (dorsal or adaxial) and lower (ventral or abaxial) surface of the leaf, and leaf portions (apical, middle, basal), as well as assess variations in the oviposition behavior of YSB and RB in different parameter

Materials and Methods

bamboo strip, with each cage measuring 1 meter in height and 1 meter in width.

Germination of Rice Seeds.

A table, tissue paper, 26 petri dishes, and forceps were used. They were also sterilized with 70% solution of commercial Ethyl alcohol. Tissue papers were placed inside the petri dishes (100x20mm). Distilled water was then used as a moistening agent for the tissue paper substrates. 13 rice varieties were germinated, namely; (NSIC Rc 216, NSIC Rc 480, NSIC Rc 442, NSIC Rc 222, NSIC Rc 160, NSIC Rc 534, NSIC Rc 506, NSIC Rc 27, PSB Rc 18, PSB Rc 82, Arabon, Calatrava, Cuevas). For each variety, two petri dishes containing 100 scattered rice seeds each were thoroughly handpicked using forceps and stored in a room under laboratory condition.

Transplanting of the Germinated Seedlings. 13 plastic pails with each pail containing 13kg of puddled soil (Guimbalaon soil series) clay loam soil type, were filled with tap water throughout the container. The soil was hand mashed until it became smooth in texture. After letting the soil settle onto the container, excess water was then drained. 10 germinated rice seedlings per variety were transplanted on each pail. All containers were plotted in rows, with a distance of 3 feet between each pail. Oviposition cages were then assembled to enclose the containers.

Acquisition of Pupae. Whiteheads on rice crops at reproductive stage from the paddy fields near the experimental site were observed. Infested stems were gently plucked with the roots intact and later dissected to examine the presence of YSB pupae. Stem segments with pupae were cut using scissors and placed in a pail partially filled with water to ensure adequate moisture content. The container was then covered with a mesh net and tied using a twine string to enclose the subject.

Acquisition of Adults.

Sweep-Net Sampling was conducted early morning in the rice fields at heading stage to ensure that an increase in temperature along with the reduction of relative humidity and minimal precipitation will be favorable for the spread of yellow stem borers and rice bugs. Sweep nets of 35 inches height and 13 inches diameter with handles 32 inches long were utilized to capture active flying moths.

Male to Female Copulation.

13 rice varieties reaching Panicle Initiation to Booting Stage that were transplanted were assembled all together and enclosed under a 3x1 mosquito net. To ensure the thriving of the rice crops throughout the egg-laying period, sufficient water was provided beforehand. Accumulated adult yellow stem borers and rice bugs were then freed inside the mosquito net to be able to oviposit on rice crops.

Collection of Eggs.

Observation of the egg masses oviposited by the moths after a week were conducted by counting the number of eggs per egg mass under a binocular stereo microscope. Prior to quantifying, the anal tuft covering of YSB’s eggs were removed using forceps and later dissected using a dissecting needle. The length and width of egg masses were also measured using a caliper. Leaf length and width were assessed using a tape measure. The preferential side and leaf portions were also evaluated in accordance with the polarity between the leaves' upper surface (dorsal or adaxial) and lower surface (ventral or abaxial) and its location (apical, middle, and basal).

Proper Disposal.

Collected eggs oviposited by the YSB and RB were placed in a medium filled with water due to its capability of causing maximum mortality to the unhatched eggs of the said species. Water immersion offers a practical and environmental friendly approach to effectively disrupt the life cycle of the test subjects. Implementing preventive measures at an early stage is crucial for integrated pest management strategies.

Data Analysis.

The data gathered were presented through a series of tables and illustrations, aiding in a comprehensive interpretation of the findings. The tables provided an inclusive overview of the data collected, presenting numerical values. The illustrations encompassed a range of carefully designed

Results and Discussion

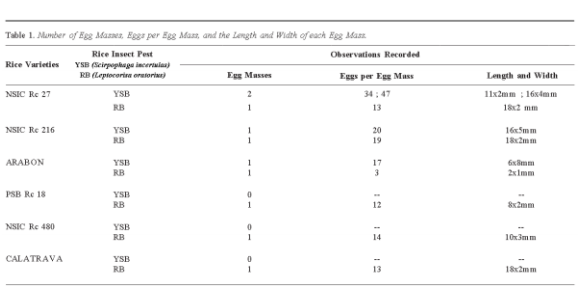

Observations on the number of egg masses, eggs per egg mass, and the length and width of each egg mass deposited by the YSB and RB on different susceptible rice varieties are presented in Table 1.

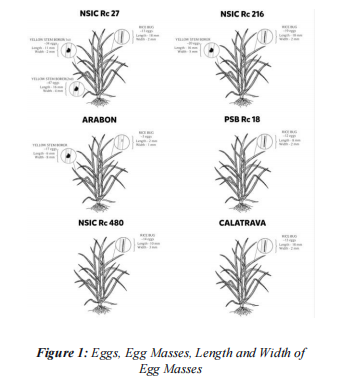

Figure 1 reveals significant variations in the vulnerability of various rice cultivars to pest infestation. The number of egg masses deposited by YSB and RB varied across the susceptible rice varieties, indicating different levels of suitability and attractiveness for sketches indicating the objectives of the study identified within the dataset.

oviposition preference [21]. Several varieties exhibited relatively higher numbers of egg masses, suggesting a greater potential for pest proliferation [22]. Others exhibited relatively lower numbers, indicating a comparatively lesser susceptibility. The length and width of each egg mass indicated the dimensions and shape of the eggs, which could have implications for their survival and viability rate [23]. Varieties that consistently displayed smaller or larger egg masses could indicate a distinction in pests' preferences and reproductive success.

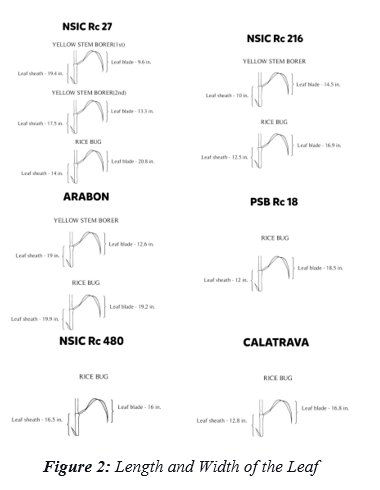

The measurements of the dimensions of rice leaves, focusing on both the leaf blade and the leaf sheath’s length and width, with particular emphasis on their length and width are presented in Figure 2.

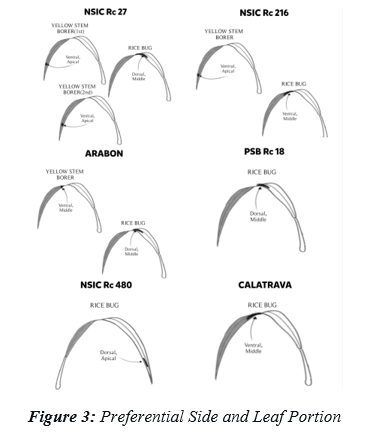

Assessment on the Preferential Side of egg masses in the parameters upper (dorsal or adaxial) and lower (ventral or abaxial) surface of the leaf and Leaf Portions (apical, middle, basal) where egg masses of YSB and RB are situated are presented in Figure 3.

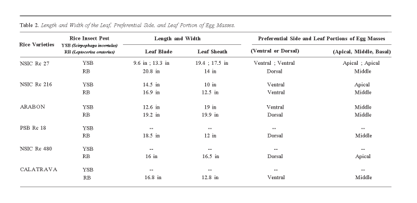

Table 2 reveals the correlation between the length and width of the leaf blade and leaf sheath where egg masses of YSB and RB were observed [24]. Greater susceptibility to both species is shown in leaves with bigger leaf blades and leaf sheaths [25]. According to the literature, a larger surface area provides a greater habitat that is more conducive to pest survival and reproduction [26]. Pests can locate more entry points suitable for feeding, laying eggs, or establishing colonies. Additionally, it might offer favorable conditions, including moisture, temperature, or nutrient accessibility [27]. A wider surface area could indicate its physiological traits, making it more appealing to pests due to chemical compositions, nutrient imbalances, and weakened defense mechanisms resulting in increased pest susceptibility [28].

Moreover, Table 2 reveals the specific regions of the leaf where the YSB and RB are most likely to deposit their egg masses. The YSB exhibits a preference for the Ventral Apical and Ventral Middle areas, which offer protection against predators [29]. This selection ensures the survival and secure development of all eggs laid in these regions. In contrast, the RB favors the Dorsal Middle, Ventral Middle, and Dorsal Apical for egg deposition [30]. This location provides quick access to the ground, reducing the time and energy needed to reach the egg-laying site.

strong

Yellow Stem Borer and Rice Bug’s Oviposition Preferences across multiple rice varieties revealed distinct patterns of susceptibility and resistance. Among the thirteen rice varieties examined, only six were found to be susceptible to these pests, with differing degrees of infestation and fecundity. Larger leaf blade and leaf sheath dimensions were associated with increased susceptibility, providing a potential indicator of vulnerability to these pests. Moreover, the specific choice of egg deposition locations by each pest indicated their strategic preferences for maximizing egg hatching and population growth.

strong

The study has yielded valuable insights, prompting several recommendations for future investigations in this field. These include conducting replicable studies across different seasons to enhance generalizability, utilizing controlled experimental environments to minimize external interferences, selecting test subjects based on species availability and abundance fluctuations, and considering the use of laboratory-reared specimens in early life stages to ensure consistent genetic backgrounds and environmental conditions.

strong

The researchers would like to express deep gratitude to their research adviser, Mr. Phillip Raymund De Oca, and experts from the Philippine Rice Research Institute for their unwavering dedication and valuable insights that played a pivotal role in the success of the study.

strong

Deka, S., & Barthakur, S. (2010). Overview on current status of biotechnological interventions on yellow stem borer Scirpophaga incertulas (Lepidoptera: Crambidae) resistance in rice. Biotechnology advances, 28(1), 70-81.

Hugar, S. V., Venkatesh, H., Hanumanthaswamy, B. C., & Pradeep, S. (2010). Comparative biology of yellow stem borer, Scirpopahaga incertulas walker, (Lepidoptera: Pyraustidae) in aerobic and transplanted rice. International Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 6(1), 160-163.

Nag, S., Chaudhary, J. L., Shori, S. R., Netam, J., & Sinha, H. K. (2018). Influence of weather parameters on population dynamics of yellow stem borer (YSB) in rice crop at Raipur. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry, 7(4S), 37-44.

Bandong, J. P., & Litsinger, J. A. (2005). Rice crop stage susceptibility to the rice yellow stemborer Scirpophaga incertulas (Walker)(Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). International Journal of Pest Management, 51(1), 37-43.

Sarwar, M. (2012). Management of rice stem borers (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) through host plant resistance in early, medium and late plantings of rice (Oryza sativa L.). J Cereals Oilseeds, 3(1), 10-4.

Chatterjee, S., & Mondal, P. (2014). Management of rice yellow stem borer, Scirpophaga incertulas Walker using some biorational insecticides. Journal of Biopesticides, 7, 143.

Hosamani, V., Pradeep, S., Sridhara, S., & Kalleshwaraswamy, C. M. (2009). Biological studies on paddy ear head bug, Leptocorisa oratorius Fabricius (Hemiptera: Alydidae). Academic Journal of Entomology, 2(2), 52-55.

Bhavanam, S., Wilson, B., Blackman, B., & Stout, M. (2021). Biology and management of the rice stink bug (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) in rice, Oryza sativa (Poales: Poaceae). Journal of Integrated Pest Management, 12(1), 20.

Naresh, J. S., & Smith, C. M. (1983). Development and survival of rice stink bugs (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) reared on different host plants at four temperatures. Environmental entomology, 12(5), 1496-1499.

Shepard, B. M., A. T. Barrion, and J. A. Litsinger. 1995. Rice-feeding insects of tropical Asia. International Rice Research Institute, Los Banos, Laguna, Philippines.

Sugimoto, A., & Nugaliyadde, L. (1995). Damage of rice grains caused by the rice bug, Leptocorisa oratorius (Fabricius)(Heteroptera: Alydidae). JIRCAS J, 2, 13-17.

Lee, S. C., Alvenda, M. E., Bonman, J. M., & Heinrichs, E. A. (1986). Insects and pathogens associated with rice grain discoloration and their relationship in the Philippines. Korean journal of applied entomology, 25(2), 107-112.

Shepard B.M., Barrion A.T., and Litsinger J.A. (1995) Rice-Feeding Insects of Tropical Asia. International Rice Research Institute, (pp. 195-202).

Jahn, G. C., Domingo, I., Liberty, M., Almazan, P., & Pacia, J. (2004). Effect of rice bug Leptocorisa oratorius (Hemiptera: Alydidae) on rice yield, grain quality, and seed viability. Journal of economic entomology, 97(6), 1923-1927.

Tripathi, S., Srivastava, P., Devi, R. S., & Bhadouria, R. (2020). Influence of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides on soil health and soil microbiology. In Agrochemicals detection, treatment and remediation (pp. 25-54). Butterworth-Heinemann.

Tudi, M., Daniel Ruan, H., Wang, L., Lyu, J., Sadler, R., Connell, D., ... & Phung, D. T. (2021). Agriculture development, pesticide application and its impact on the environment. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(3), 1112.

Kumari, A., & Kaushik, N. (2016). Oviposition deterrents in herbivorous insects and their potential use in integrated pest management.

Cury, K., Prud’homme B., & Gompel N. (2019). A short guide to insect oviposition: when, where and how to lay an egg. Journal of Neurogenetics, 33 (2), pp.75-89.

Riddick E.W., Dindo M.L., Grodowitz M.J., & Cottrell T.E. (2018). Oviposition Strategies in Beneficial Insects. International Journal of Insect Science. 10.

Devendra, C., & Chantalakhana, C. (2002). Animals, poor people and food insecurity: opportunities for improved livelihoods through efficient natural resource management. Outlook on Agriculture, 31(3), 161-175.

Reay-Jones, F. P. F., Wilson, L. T., Showler, A. T., Reagan, T. E., & Way, M. O. (2007). Role of oviposition preference in an invasive crambid impacting two graminaceous host crops. Environmental entomology, 36(4), 938-951.

Pitre, H. N., Mulrooney, J. E., & Hogg, D. B. (1983). Fall armyworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) oviposition: crop preferences and egg distribution on plants. Journal of Economic Entomology, 76(3), 463-466.

Leyva, K. J., Clancy, K. M., & Price, P. W. (2000). Oviposition preference and larval performance of the western spruce budworm (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae). Environmental Entomology, 29(2), 281-289.

Mochida, O. (1964). On oviposition in the brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens (Stål)(Hom., Auchenorrhyncha) II. The number of eggs in an egg group, especially in relation to the fecundity. Japanese Journal of Applied Entomology and Zoology, 8(2).

Thornton, I. W. B., Marshall, A. T., Kwan, W. H., & Ma, Q. (1975). Studies on Lepidopterous pests of rice crops in Hong Kong, with particular reference to the yellow stem-borer, Tryporyza incertulas (Wlk.). PANS Pest Articles & News Summaries, 21(3), 239-251.

Zheng, W.J.; Liu, Z.H.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Liu, X.; Wang, C.H.; Zhao, J.M. Effects of the major nutritional substances and micro-structure of rice plants on the host preference of the small brown planthopper, Laodelphax striatellus. Acta Phytophyl. Sin. 2009, 36, 200–206.

Heisswolf, A., Obermaier, E., & Poethke, H. J. (2005). Selection of large host plants for oviposition by a monophagous leaf beetle: nutritional quality or enemy‐free space?. Ecological Entomology, 30(3), 299-306. nal quality or enemy‐free space?. Ecological Entomology, 30(3), 299-306.

Sarwar, M. (2011). Effects of Zinc fertilizer application on the incidence of rice stem borers (Scirpophaga species)(Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) in rice (Oryza sativa L.) crop. Journal of Cereals and Oilseeds, 2(5), 61-65.

Xian Rong Ling, A., Kuok San Yeo, F., Hamsein, N. N., Ting, H. M., Sidi, M., Ismail, W., ... & Cheok, Y. H. (2020). Screening for Sarawak Paddy Landraces with Resistance to Yellow Rice Stem Borer, Scirpophaga incertulas (Walker)(Lepidoptera: Crambidae). Pertanika Journal of Tropical Agricultural Science, 43(4).

Cobblah, M. A., & Den Hollander, J. (1992). Specific differences in immature stages, oviposition sites and hatching patterns in two rice pests, Leptocorisa oratorius (Fabricius) and L. acuta (Thunberg)(Heteroptera: Alydidae). International Journal of Tropical Insect Science, 13(1), 1-6.