Physically and Chemically Characterized Fibers as Indigenous Water Filters

| Authors | Christopher John M. Tuble II, Julius Ian Gabriel T. Bayoneta, Robert Grey A. Hudierez, Phillip Raymund R. De Oca, June Nathan M. Fernandez |

|---|---|

| Volume | 1 |

| Date Published | September 27, 2021 |

| Date Updated | September 21, 2024 |

Abstract

The dwindling supply of clean water is one of the most crucial problems affecting the world today, in a bid to make clean water, coined to investigate the physical and chemical properties of pineapple, abaca, and coir fibers for filter applications and its capability to reduce or remove water bacteria when used as a filter. The obtained fiber filaments' pH level, tensile strength, density, and moisture content ranged from data reported in the literature, yielding good and potential values fit for the stated purpose. The pre-and post-analysis of the water samples through bacterial heterotrophic plate count and total coliform count by culture-based methods using selective media indicated a considerable reduction in bacterial counts after filtering the water samples. The quantity of bacterial reduction and removal varies with fibers used; hence, abaca fiber is significantly superior to, coir and pineapple.

Introduction

Having access to safe drinking water is a basic human right [1-3]. It is identified as one of the prerequisites to achieving numerous dimensions of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including health, food security, and poverty reduction with population growth, agricultural intensification, urbanization, and industrial production [4]. The United Nations World Water Development reported that by 2025, the planet would face a complete water deficiency. The earth lacks adequate sanitation, and the available freshwater has amounted to less than one-half of 1% of all the water [5] [6].

Being an archipelago, different water bodies surround the Philippines. However, clean and accessible water remains an elusive commodity. According to Dr. Gundo Weiler, WHO Representative in the Philippines, Filipinos are still being left behind in accessing improved water sources [7].

The majority of Filipinos living in the urban area opted to buy purified or distilled water instead of tap water for drinking [8]. On the other hand, over 15% of the country's rural communities do not have access to potable water due to limited income. Natural groundwater serves as their source of drinking water [9].

However, due to its qualitative changes, it is incorrect to presume that groundwater is generally safe [10]. One hindrance to nature's ability in supporting the potable water demand is the significant increase in toxic waste being dumped in land and water bodies. As a result, water contains waterborne bacteria that cause disease outbreaks that are detrimental to human health. In 2015, the Philippine Statistics Authority reported 3,240 cases and 44 deaths caused by waterborne diseases such as diarrhea, cholera, dysentery, and hepatitis A [11].

When it comes to water, which is a basic commodity, people cannot afford to disregard the issues. Thus, the best approach to solving such issues is to develop a product that may let people have cleaner water to use sustainably and less costly; as a result, the researchers opted to develop a water cleanser made from indigenous materials. The choice of using indigenous materials conveys support in making the world eco-friendly. Among the natural plants that produce fibers in the locality, a pineapple leaf, abaca, and coconut coir because of accessibility and properties like their being lightweight, non-abrasive, non-toxic, low cost, renewable, recyclable, biodegradable, and carbon dioxide neutral [12] [13].

This study investigates the physical and chemical characteristics of a pineapple leaf, abaca, and coir as used in an indigenous water filter. It also determines these fibers' capacity as an indigenous water filter to reduce microbial bacteria present in deep well water. It intends to determine if the water bacteria number varies when undergoing the filtration process considering the mass and type of fibers used.

Methodology

This descriptive research entails three stages of investigation: material preparation to make a fiber thread from pineapple leaves, abaca, and coir followed by experimentation on chemical properties, particularly on acidity, moisture content, and the physical properties through density and tensile strength of the fibers, and the determination of its capacity as an indigenous filter to absorb water bacteria using appropriate statistical tools.

Extraction of Indigenous Fibers

Applying a ceramic plate over the leaf with pressure and fast mechanical movement mechanically extracted the pineapple (Ananas comosus) lead fibers. The procedure slowly produced threads from the leaf for hand-picking [14]. For abaca (Musa textilis) fiber, after harvesting its stalks, fibers were extracted from the leaf sheaths through hand stripping, separated manually from other components of a stalk. [15]. Coir (Cocos nucifera) was extracted from the tissues surrounding the seed of mature coconuts. The fiber was removed mechanically using hand shedding. The traditional method was applied in this study as it produces quality threads [16]. The extracted fibers were left out to dry naturally in the sun.

Physical and Chemical Characterization of the Fibers

The test of the fiber’s physical and chemical characteristics was done at the laboratory of one of the Higher Educational Institutions (HEIs) with a laboratory technician's aid under the supervision of a licensed pharmacist and a physics teacher. In determining fiber density, this study used the Archimedes Principle. The fibers were weighed equally and put into the graduated cylinder. 100mL of distilled water was added to the graduated cylinder via a burette. The volume of water added to the graduated cylinder was recorded as the volume (V) of distilled water displaced. Thus, the density of the fiber obtained was estimated using this equation:

𝐹𝑖𝑏𝑒𝑟 𝐷𝑒𝑛𝑠𝑖𝑡𝑦 = M/V

For the density test for natural fiber, literature states that the best result should be between 0.8 –1.5; this is the suitable density range for long natural fiber [17]. The tensile strength test would evaluate the maximum stress that a material can endure while being stretched or pulled before necking. This test usually involves taking a small sample with a fixed cross-sectional area by dragging it with controlled force, gradually increasing the pressure until the sample changes its shape or breaks [18]. Each fiber was tied to an iron ring attached to the iron stand. Masses were gradually added until fiber strands break. In each sample, load value (F) was recorded until a break of the specimen occurred. The fiber diameter, recorded in mm, was ascertained using the microscopy method. Tests were done in three (3) trials for accurate data. Mathematically using the values obtained, tensile strength of the fiber was determined using the formula below:

= Force (Kg) / Stress Area of the Specific diameter (mm)

The acidity and moisture content were observed and recorded to determine the chemical characteristics of the pineapple leaf, abaca, and coconut coir fibers. For the fiber’s acidity, the pH level test would determine whether the thread was suitable for making the filter. Steps required soaking the fibers that were cut into small pieces in 20 mL warm distilled water for 10 minutes and then recording its pH level. For the fiber’s moisture content, a digital moisture analyzer was used to ascertain how much water is in it. The researcher loaded each fiber type in three trials in a sample plate and allowed the equipment to heat the sample using a 400W Halogen quartz glass heater at 120 0C. The equipment automatically analyzed the moisture content at a constant time.

Filtration Process

Fibers were subjected to sterilization. After such, it was weighed as to 5 and 10 grams per type, respectively. The fiber was rolled into a round and put in the sterilized funnel open mouth l attached to the sterile bottle. Deep well water was poured gradually in the bottle through a funnel with indigenous fiber functions as a filter.

Determination of the Capacity of the Indigenous Filter to Lessen or Eliminate Waterborne Bacteria

Experimentation was done in an ISO/IEC accredited diagnostic and analytical laboratory in the locality with the licensed chemist using seven (7) set-ups. One set-up was for a deep well water sample, noted as the pre-test. The remaining six set-ups were for post-tests. Deep well water samples underwent a filtration process using 5g and 10g of pineapple, abaca, coir fibers. The water samples are tested for bacteriology count. Three replicates per set-up are performed to have accurate data with regard to the total count of bacteria present in deep well water and with set-ups that use fibers as an indigenous filter. The bacteriological parameter used in the total bacterial count is Heterotrophic Plate Count through the Pour Plate Method using Plate Count Agar. The normal plate count for potable water is 25-250 CFU’s[19]. Furthermore, to assess the specific pathogens present in the water sample, a Total Coliform count was conducted through Compact Dry Media (AOAC) method. The Colony Forming Unit (CFU)/mL presented the result. The samples were tested within eight (8) hours after its collection. Mean was used as a descriptive tool to establish physical and chemical fiber characteristics and determine the fiber capacity in lowering the microbial bacteria present in a water sample when used as a filter. Two-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with Repeated Measures was used as an inferential tool to determine if significant differences occur in the percentage of water bacteria reduction than the fiber type and the amount of mass used filters.

Results and Discussion

Physical and Chemical Characteristics of Indigenous Fibers

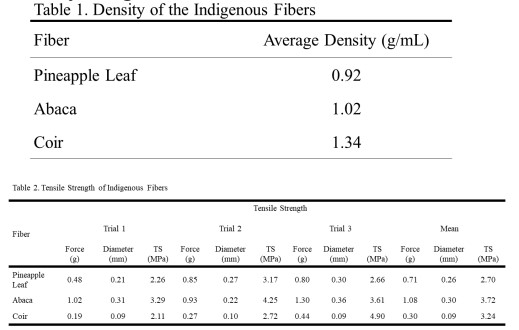

For the fiber density, the result in Table 1 entails that the fibers extracted from the pineapple leaf obtained an average density of 0.92g/mL, abaca fiber with 1.02g/mL, and coir fiber of 1.34/mL from three trials. The result is within natural fiber densities of 0.8–1.5 as it ensures the right mass. The thickness of the pineapple leaf, abaca, and coir fibers is within the standard density range of natural fibers.

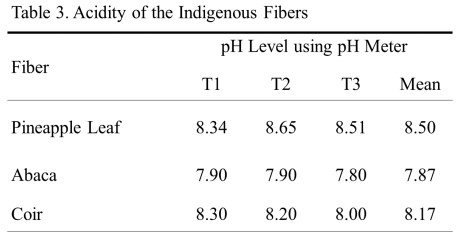

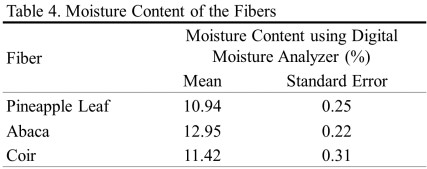

Table 2 presents the tensile strength of the pineapple leaf, abaca, and coir fibers. Based on the obtained results, abaca fiber is the strongest among the three fibers with the tensile strength of 3.72MPa, followed by coir with 3.24MPa and pineapple with 2.70MPa. The amount of force each fiber could hold until it breaks causes the tensile strength mean score variation. The standard tensile strength of the natural fiber is 30MPa [20]. The result implies that the indigenous fibers are below the standard. The natural fiber’s chemical makeup varies greatly and depends on the source and processing methods [21]. Furthermore, the indigenous fiber’s chemical characterization tested its acidity and moisture content. As presented in Table 3, the pineapple leaf fiber obtained an average pH level of 8.50, abaca fiber with 7.87, and the coir fiber with 8.17. Pineapple leaf has the highest level of acidity compared to coconut coir and abaca. Mean scores that range between 7-9 denote that fibers are within the acceptable standard of groundwater’s pH level, which is 6.5-8.5.

Results in Table 4 show the average moisture content of the indigenous fibers after three trials and its standard error. The pineapple leaf fiber obtained a weighted mean score of 10.94% with a standard error of 0.25%, abaca fiber with 12.95% and a standard error of 0.22%, and coir fiber with 11.42% and a standard error of 0.31%. The range for the natural fiber to be of acceptable quality is 6–15%.

The Capacity of Indigenous Filters to Reduce Waterborne Bacteria

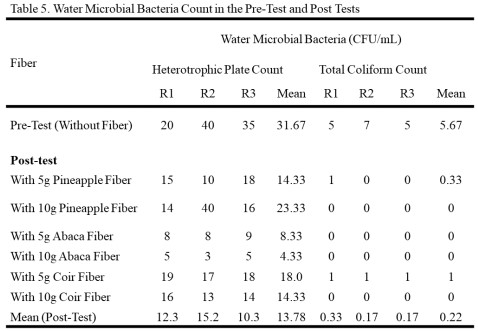

Data in Table 5 shows the microbial bacteria number present in deep well water samples during pre-and post-tests. The deep well water Heterotrophic Plate Count of bacteria in three (3) replications attained an average of 31.67. The water sample analysis detected Coliform presence ranging between 5-7CFU/mL of water. Filtering by indigenous fiber, 44% of the heterotrophic microorganism population was reduced using the pineapple leaf, abaca, and coir fibers in various masses as evidently shown by the post-test mean score 13.78 CFU/mL from 31.67 CFU/mL of the pre-test. The abaca performed well among the three fibers, indicated by mean scores of 8.33 (5g filter) and 4.33 (10g filter), respectively. As the mass of the abaca fiber filters increases, heterotrophic bacteria quantity decreases. Thus, the performance to lessen the bacteria depends on the fiber type used. In the total coliform count, a considerable decrease from 5.67CFU/mL to 0.22CFU/mL is seen when the water sample was subjected to filtration using indigenous fibers of varied masses. Data entails that among the three fibers, abaca, regardless of using either 5g or 10g denomination, could trap 100% of the coliform bacteria. The same result is observed in treating water with 10g of pineapple and coir fiber filter. Pineapple and coir also have the capacity of trapping coliform bacteria with mean scores of 0.33CFU/mL for 5g pineapple leaf fiber and 1CFU/mL for 5g coir. The result signifies that natural fiber such as the pineapple leaf, abaca, and coir as indigenous filters could lessen or eradicate coliform bacteria present in groundwater. Regardless of the fiber type and mass used, water laboratory analysis after filtration was within the acceptable values defined by the Philippine National Standard Drinking Water of <1.0 MPN/100mL [22] [23].

The Difference in the Capacity of the Indigenous Filters to Reduce Waterborne Bacteria as to Type and Mass of Fibers

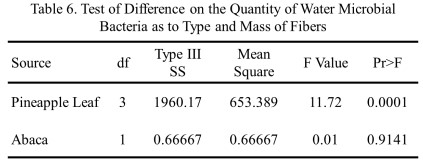

Table 6 shows a significant difference in the microbial bacteria number using heterotrophic plate count as to the type of fibers and mass used. Data shows that the type of fibers obtained an F value of 11.72 and p-value of 0.0001, which is significant at 0.05 level. The result denotes that the fiber types have significant bearing on reducing the number of bacteria present in the sample water. No significant difference is noted with the p-value of 0.914>0.05 alpha when mass is considered. This means that the quantity of the microbial bacteria reduction after filtration is most likely the same, whether by using 5g and 10g fiber filters. From this, it is conclusive that only the fiber type accounts for the variability in the bacterial count using HPC, not their mass. Abaca significantly possesses the lowest bacterial count after filtering, with pineapple and coir, respectively. Thus, the fiber filter is effective in treating unclean water with minimal cost and high efficiency. The purification process using pineapple, abaca, and coir fibers proceeds via an ion exchange mechanism between the OH of the cellulose in the fibers with metallic ions and the organic group as impurities in the unclean water [24].

Conclusion

Pineapple, abaca, and coir fibers have the potential as a filament to be used as a water filter. Acidity and moisture content shows that the bio-fibers are within the acceptable level, and each fiber is elastically condensed and strong enough to withstand the flow of water. The fibers can easily be used as an effective filter for absorbing water bacteria present in groundwater. Abaca fiber reduces the bacterial count in filtering raw water over pineapple and coir. The study's indigenous fibers significantly reduced the coliform count when used as filters. A significant difference exists in its capacity to mitigate waterborne bacteria when the fiber type is considered. However, the filter mass does not significantly contribute to the mean coliform filtration. Thus, regardless of mass, the fiber filter can reduce or even eradicate coliform bacteria at the same level.

Recommendations

Based on the findings, pineapple, abaca, and coir fibers have the physical and chemical characteristics capable of reducing bacteria when used as a water filter. To improve quality and application, more study should be done on the biotechnological, chemical characteristics, and engineering elements of the fibers; further research is needed to significantly improve the chemical properties of the fiber thread for more flexibility and durability. The kinetics and mechanism of the natural fibers’ moisture be considered since fiber filters will be frequently exposed to liquid.

References

- De Vido, S. (2012). The right to water as an international custom: The implications in climate change adaptation measures. Carbon & Climate Law Review: CCLR, 6(3), 221-227. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/1271859002

- Dattarao, J. V. (2012). The human rights to safe drinking water and sanitation. Asia Pacific Journal of Mngt & Entrepreneurship Research, 1(1), 45-52.

- Halving Proportion of People Without Sustainable Access to Safe Drinking Water Major Achievement. (2012, Mar 13). US Fed News Service. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/newspapers/halving-proportion-people-without-sustainable/docview/927606482/se-2?

- United Nations (UN) (2018). The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2017; United Nations:New York, NY, USA.

- United Nations Department of Economics and Social Affairs (UNDESA) (2014). Coping with water scarcity. Challenge of the twenty-first century. UN-Water, FAO. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/waterforlifedecade/scarcity.shtml

- United Nations Division for Sustainable Development Goals Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2018). Sustainable Development Goal 6: Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all. Retrieved from https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2018/Goal-06/

- World Health Organization Representative Office for the Philippines (2019). Water shortage in the Philippines threatens sustainable development and health. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/philippines/news/feature-stories/detail/water-shortage-in-the-philippines-threatens-sustainable-development-and-health

- Rebato ND, de Los Reyes VCD, Sucaldito MNL, Marin GR. Is your drinking water safe? A rotavirus outbreak linked to water refilling stations in the Philippines, 2016. Western Pac Surveill Response J. 2019 Feb 20;10(1):1-5. doi: 10.5365/wpsar.2017.8.1.007. PMID: 31110836; PMCID: PMC6507125.

- Gomez M, Perdiguero J, Sanz A. (2019). Socioeconomic Factors Affecting Water Access in Rural Areas of Low and Middle-Income Countries. Water. 2019; 11(2):202.

- Krishnan, S. (2009). The silently accepted menace of disease burden from drinking water quality problems. CAREWATER, INREM Foundation, Anand. Retrieved from GoogleScholar.

- Water Borne Diseases Cases and Deaths - Philippine Statistics Authority https://psa.gov.ph/.../Table%205.4.4%20Water%20Borne%20Diseases%20Cases%20a

- Thakur V. K. & Singha, A.S. (2013). Biomass-based Biocpmposites. United Kingdom: A Smithers Group Company.

- Razi, M. B. (2015). Effects of Pineapple Leaf Tube Length on the Properties of Pineapple Fiber-Starch Composites. Universiti Teknical Malaysia Melaka.

- Pradeep,Paladugula & Dhas,J.(2015). Characterization of Chemical and Physical Properties of Palm Fibers. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering: An International Journal (MSEJ). 2. 01-06. 10.5121/msej.2015.2401.

- Armecin, R.B. & Coseco, W.C. (2012). Abaca allometry for above-ground biomass and fiber production, Biomass and Bioenergy, V46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2012.09.004.

- Kamarudin, Z., Farhana, N. and Yusof, M. (2016). Pineapple Fibre Thread as a Green and Innovative Instrument for Textile Restoration. International Journal Sustainable Future for Human Security J-SustaiN. Vol.4;No.2;p 30-35 http://www.j-sustain.com

- Prado, K. & Spinacé, M. (2015) Characterization of Fibers from Pineapple’s Crown, Rice Husks and Cotton Textile Residues. Materials Research 18(3):530–537 10.1590/1516-1439.311514.

- Murali Mohan Rao, K, Mohana Rao, K. Extraction and tensile properties of natural fibers. Compos Struct 2007; 77: 288–295. Google Scholar | ISI

- Bartram, Jamie. (2003). Heterotrophic Plate Counts and Drinking-water Safety: The Significance of HPCs for Water Quality and Human Health.10.2166/9781780405940.

20.Rowell, R.M.(2012). “Opportunities for Lignocellulosic Materials and Composites”, Chapter 2 of Emerging Technologies for Materials and Chemicals from Biomass American Chemical Society, Washington, DC.

- Ottenhall, A., Ottenhall, J. & Illergård, M. (2017). Water purification using functionalized cellulosic fibers with nonleaching bacteria adsorbing properties. Environmental Science & Technology, 51 (13).

- Mwabi J. K, Mamba B.B and Momba MNB (2012). Removal of Escherichia coli and faecal coliforms from surface water and groundwater by HWTS: A sustainable solution for improving water quality in rural communities of the SADC region. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 9 (1) 139-170.

- Mwabi, J. K., Mamba, B. B., & Momba, M. N. B. (2013). Removal of waterborne bacteria from surface water and groundwater by cost-effective household water treatment systems (HWTS): A sustainable solution for improving water quality in rural communities of africa. Water S. A., 39(4), 445-456.

- Isogai, A. (2018). Development of completely dispersed cellulose nanofibers. Proceedings of the Japan Academy, 94(4), 161-179. Retrieved from doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.2183/pjab.94.012